Become a business-aware designer

In 2021, design is no longer an afterthought. The popularity of ideation sessions and design sprints, programs like Stanford’s D.School and frameworks like IBM’s Enterprise Design have meant that ‘design’ is being seen as a required input to get a competitive edge.

As Google’s Kate Aronowitz puts it: designers finally have a seat at the table.

It’s a change that’s been incredibly successful. One example: at the end of last year, Airbnb’s share price surged on the day of their IPO, leaving them with a valuation of more than $100bn. Airbnb is a company that is proudly design-led (as opposed to other unicorns that focus foremost on product engineering). They regularly publish detailed articles and videos about their design process.

And other companies are adopting these processes. Netflix, Uber, Microsoft, PepsiCo and Ikea are all big companies that are increasingly turning to design thinking processes and paradigms to solve problems in their industries.

But, despite design being used as a differentiator for many companies, it’s still something optional. Companies have been creating products and services at a huge scale over the last three decades. Many have been able to do so without design leaders in the room, solely using a combination of business and engineering expertise.

Design does give companies an edge… but new designers need to be aware that they’re joining a pre-existing conversation.

So, what is the best way for designers to join that conversation?

Answer: by becoming a business-aware designer.

Ryan Rumsey, writing for InVision’s Design Better series, asserts that the most successful designers are the most business-aware. Having designers who understand the language and tactics of business allows them to be more involved in strategic decisions, and therefore to have a bigger impact.

And, Alen Faljic from d.MBA points out that:

understanding business and becoming fluent in business language will make it easier to convince non-designers into user-centric ideas.

So here are five ways to become a business-aware designer:

1. Know the basics of business #

Companies exist to make money. That’s the bottom line. Complain about it if you want, but capitalism is the reality of modern society, and it’s here to stay.

Over the course of a year, a company makes money by making more profit.

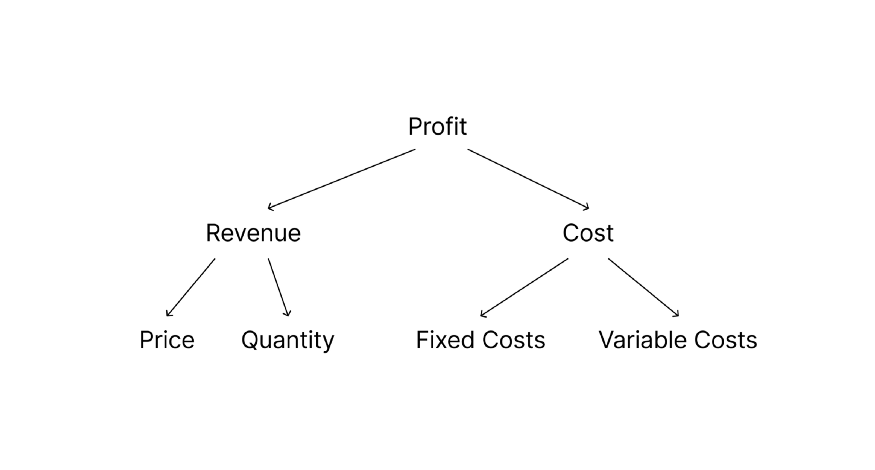

Profit is a simple function of revenue and cost; it’s equal to the total revenue earned minus total costs spent.

- There may be one sole revenue stream, or multiple revenue streams. For a company that makes money by selling a single individual product, revenue is a product of quantity of that item sold x cost per item.

- Costs are usually broken down into fixed costs and variable costs. Fixed costs are the same no matter how much the company sells; variable costs vary based on how much is sold (among other factors).

Breaking down the cost/revenue model for your company (or branch of the company, or specific product) is a really great way to start thinking about how design decisions affect the core business model.

Put simply: every decision should eventually end up increasing revenue or decreasing cost.

It’s worth pointing out that, because many design-oriented companies are startups (or have a startup-mindset), they may not be as revenue-driven as other companies.

Generally speaking, most startups are focussed on increasing growth, and are working on the basis of finding a revenue model later once they have critical mass. For companies with a growth-focus rather than a profit-focus, user acquisition will be more important than just increasing revenue or cutting costs. So for these companies, every decision should eventually end up increasing the number of users.

2. Be mindful of the wider industry and competitors #

It’s so important to have the right context in mind when designing or building anything.

Designers will usually perform a competitor analysis exercise. This involves researching direct and indirect competitors, examining the latest visual trends, exploring popular features being added, digging into new platform changes (iOS 14 widgets anyone?), and so on.

However, it’s also worth being aware of what it means to analyse competitors from a business perspective.

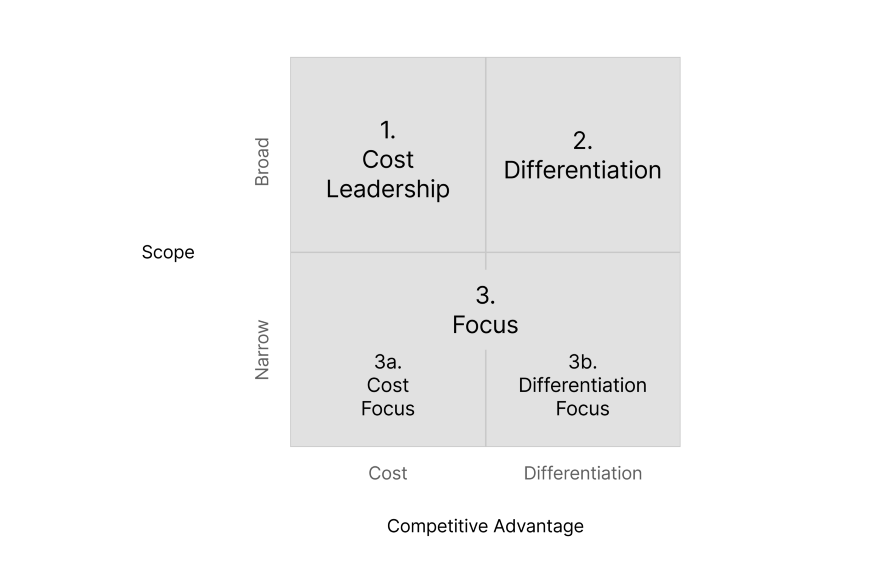

Michael Porter’s 1985 book, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, outlined three general strategies that a business could use to find a competitive advantage in their industry. They can be applied to products or services in all industries, and to organizations of all sizes.

They are:

- Cost Leadership

- Differentiation

- Focus

It’s worth reading this detailed breakdown from MindTools about the three strategies, but I’ll summarise them below.

The first strategy is to become a ‘cost leader.’ This means reducing your company’s costs to get the edge over competitors. The can either be done by reducing the cost of your products, to gain more sales, or by reducing other costs and maintaining industry-average prices.

This requires more than just setting prices lower. It requires an investment in technology and logistics so that costs can sustainably stay lower than those of competitors.

The second is to create differentiation. Your company’s products should stand out from those of your competitors, meaning they’re seen as more attractive in the eyes of a consumer.

The third strategy is to focus on a niche customer base. Undertstanding the specific market and customers allows a company to create unique, fit-for-purpose products for that market. A focus strategy is not enough on its own, so its still essential to decide whether to pursue a cost leadership or differentiation strategy as well.

3. Make use of business tools and frameworks #

We all know that UX designers love a good canvas. Here are two tools that will feel familiar but have more of a business-focus to them. A lot more could be written about each of these; here I just detail the basics of what they are.

Alex Osterwalder created a widely used one-page business model canvas which has been improved and adapted a few times. My favourite improvement on this is Ash Maurya’s canvas, widely used by startup accelerators like Techstars.

I’ve created a replicable version of this canvas in Figma with instructions on how to use it, which you can get here.

This framework comes from Oliver Gassman’s book The Business Model Navigator. It helps you answer four key questions. Who are your company’s target customers? How does your company deliver value for them? How does your company create that value? How does your company, in turn, capture that value?

This is more useful for a company that’s looking for areas in which to innovate; the above canvas is better for brand new companies (startups) that are running lean.

Again, I’ve created a replicable version of this framework in Figma with instructions on how to use it, which you can get here.

4. Communicate with metrics #

Data is hugely important and something I’ve only really started to appreciate. But it all comes down to this: if you can’t measure something, you can’t improve it.

Kerry Rodden from Google Ventures advocates design which is data-informed rather than data-driven. Data doesn’t take over; instead it serves to inform the design process.

Her article explains how to use Google’s HEART framework to identify goals, signals and then metrics which are relevant to your product. She writes:

If you measure adoption and retention [as well as unique users] you will be explicitly distinguishing new users from returning users, so you can tell how quickly your user base is growing or stabilizing. This is especially useful for new products and features, or those being redesigned.

Think about data and metrics both in terms of business as well as design. Tying back to the first point, how do the metrics you’ve chosen to track align with the company’s overall goals (increasing profit / increasing growth)?

Framing metrics in these terms will get you more buy-in. Your design activities therefore not only help improve a user’s experience, but also makes the business better.

While tracking metrics is important, it’s easy to get lost if you’re worrying about too many at the same time.

That’s why it’s also important to identify what’s called a North Star metric. This is a single indicator that measures what success is for your company. It could be the number of referrals, number of conversions, number of matches, time spent on app; it’s just whatever makes sense for your company.

(And, as you’d expect, there’s a framework to help you work out what your North Star metric is.)

5. Talk the talk #

Lastly, it’s important to know business vocabuary and be able to use it confidently.

Since starting my own startup late last year, I’ve learnt a ton more about the business side of running a company. With that comes an ability to express myself using terminology I never understood before.

There’s no way to rote-learn this, but just being aware of this language and looking things up when they’re new to you is a great way to start.

Some phrases it’s worth knowing as a starting point: competitive advantage, profit margin, market forces, disintermediation, low touch, and razor blade/reverse razor blade.

Thanks for reading this guide! I hope this sets out the basics of how to become a better designer by being more aware of the business implications and strategic decisions that your design will impact.

If there’s anything I’ve missed, comment below or message me on Twitter. I’m always looking for new resoruces and ways to improve!

Futher reading:

- 7 Things Designers Should Know About Business

- Business Thinking for Designers

- Eliminate executive interference to get your innovative ideas out

Thanks for reading! Read more articles tagged Design, or check out everything.