My master’s thesis

Share:

I recently completed my degree at the University of Oxford. My undergraduate and masters were combined, so I’m only getting one degree, instead of a BA and a Masters separately. The degree title is Master of Computer Science and Philosophy.

The fourth year of the course was split into three parts. One third was a 20,000 word thesis; I wrote it comparing an aspect of Advaita Vedanta (maya or avidya) in the writings of Adi Sankaracharya, with a very similar idea in the philosophy of a German 18th century philosopher called Schopenhauer.

I have included an extract of my thesis below. If you want to read the full thing, please don’t hesitate to message me!

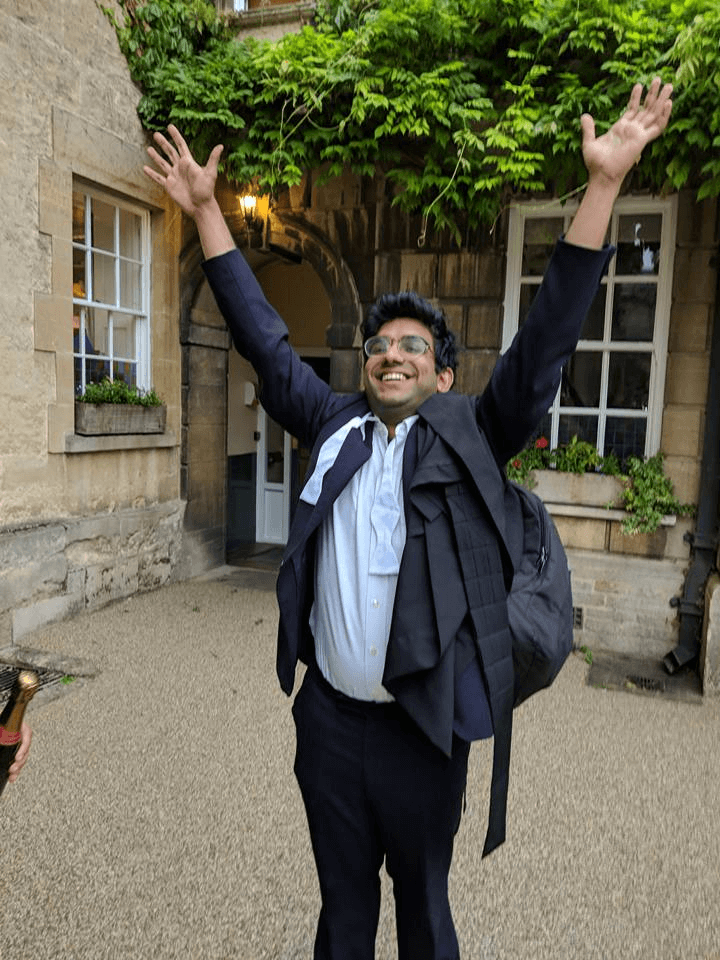

The other two thirds were two modules. For each, I had to sit a 3h45m exam and submit a 5,000 word extended essay. My exams ended up being on the same day (🙁), so a few weeks ago I sat 7h30m of exams in one day, with a small break in the middle for lunch. Below are some photos of me finishing those exams.

End of a long day of exams

End of a long day of exams

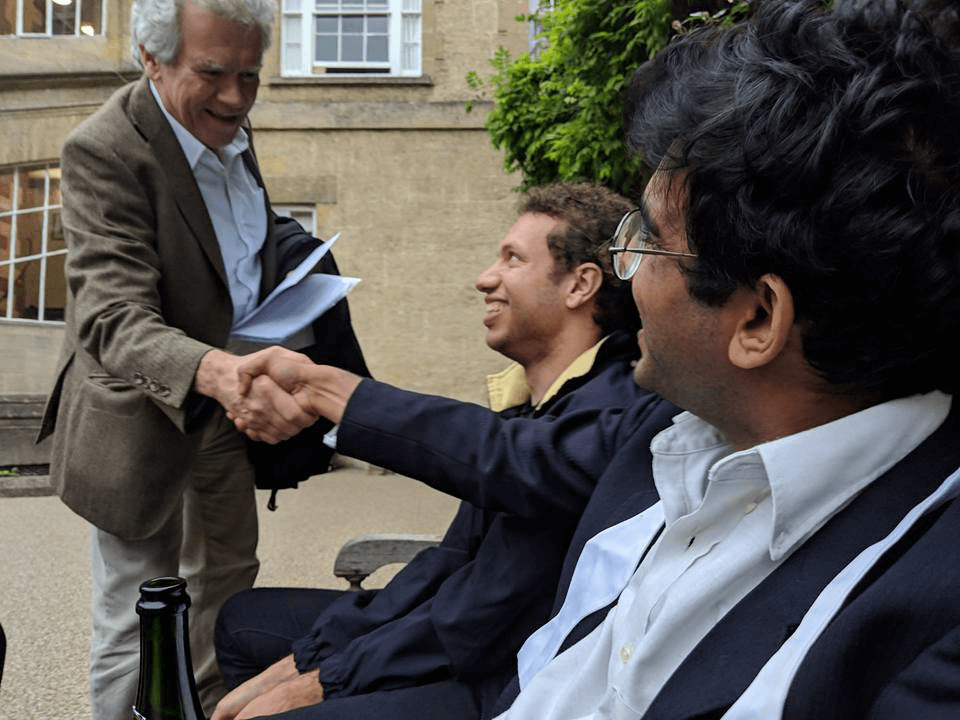

My tutor, Peter, who was the reason I made it through my degree

My tutor, Peter, who was the reason I made it through my degree

Thesis Introduction

In this thesis, I compare two philosophers: the 19th century, post-Kantian philosopher Schopenhauer, and Sankara, an ancient Indian philosopher from the 8th century. I examine their respective theories of representation and the arguments that they each give in defence. Sankara’s theory is that the world which we experience is illusory in nature, resulting from an individual’s ignorance (avidya) of their true nature. Schopenhauer’s theory is a type of idealism, labelled by him as the ‘representation’ aspect of the world, or the ‘world as representation.’

Examining the relationship between two philosophies can proceed in different ways. The first is by questioning whether one developed under the influence of the other. This is done by examining historical and textual evidence. The second is a comparative approach. This is done through a critical analysis of the arguments used to defend each philosophy; the strategies or flaws of each is used to strengthen or attack the other. Such a comparison can be undertaken without historical consideration. Much has been written on the influence of Indian philosophy on Schopenhauer’s writings; this thesis instead proceeds using a comparative approach.1

I aim to analytically discuss and evaluate arguments given by Schopenhauer and Sankara. Their respective styles of writing present a challenge: they write in different contexts and are guided by different motives. Here I aim to bring out the essence of their philosophical works in a way which allows them to be dissected and to be compared with each other: in the first part, I do this by enumerating the key tenets of their theories; in the second part, I do this by syllogising their arguments into premises, allowing for an examination of validity and assumptions made.

Schopenhauer had a lot in common with Indian philosophy. Magee writes that “[t]here is nothing controversial in saying that of the major figures in Western philosophy, Schopenhauer is the one who has most in common with Eastern thought.”2 Choosing Sankara to compare him to is due to his influence and reputation. He is credited with establishing and unifying large sections Hindu philosophy,3 and is labelled as one of the founding fathers of Advaita Vedanta.4 His writings attempt to systematise early Hindu ideas; he also defends these ideas using methods of reasoning found in the earlier Buddhist Mādhyamika philosophy.5 Furthermore, a comparative study of schools of philosophy can only be done meaningfully when working within a limited scope. There exists a huge range of Indian thought, and so by focussing specifically on Sankara’s writings and the Advaita Vedanta school, this discussion can take place.

I choose to focus on theories of representation due to their continuing relevance in philosophy. A theory of representation explains all experience of the empirical world by positing that we perceive one thing which is merely a representation of something else.6 Both Sankara and Schopenhauer claim that all we ever do perceive are representations; the underlying ultimate reality is something else entirely. Questioning whether our world of everyday objects could be unreal is something that challenges philosophers even now. Moreover, it is a question that has a relevance beyond philosophy: it inspires and challenges poets, artists and authors.

The Indian philosophical texts which Schopenhauer read were only available to him in a double-translation: from the original Sanskrit into Persian, and then into Latin. These translations are considered to be outdated and inaccurate.7 Thus, to facilitate the most accurate comparison, the primary sources I refer to are contemporary translations into English of both Sankara’s and Schopenhauer’s writings.8

Translations given will prioritise philosophical clarity over accuracy of translation. Key Sanskrit terms will be transliterated and provided alongside their translation into English.9 After their first use, I use English translations. The exception to this is my use of the term avidya; as I explain in Section 4, it does not have a direct translation. Many Sanskrit terms have different meanings depending on context, and hence warrant different translations depending on the school of philosophy they are used in; in what follows I give the translation appropriate to their use in Advaita Vedanta.

This thesis proceeds in two parts: the first part examines the two theories, and the second part examines the arguments given to defend the theories. In the first part, Sections 2 and 3 cover the backgrounds of Sankara and Schopenhauer in detail, providing a context for each of their theories. Sections 4 and 5 then explain each of their respective theories of representation, and Section 6 notes similarities and differences between the theories when examined in themselves. In the second part, Section 7 enumerates the arguments given by each to argue in favour of the theories; from this list, I choose five arguments to examine. Section 8 examines one of the arguments used by Schopenhauer, namely the dream argument, and Section 9 examines two similar arguments made by Sankara. Then, Section 10 examines another one of the arguments that Schopenhauer uses, namely the argument from causality, and Section 11 examines a similar argument from Sankara. Section 12 concludes with a summary of my findings.

My examination reveals that, as Schopenhauer himself claimed, the two positions really are very close, to the extent that they even make use of structurally similar arguments. My conclusion lists a number of similarities and differences.

Concerning the theories when examined in themselves, I argue that they are, in essence, identical, and that the main differences are about the knowability of the ultimate reality and Schopenhauer’s pessimism.

Concerning the arguments given to defend their theories, I list certain structural similarities in their styles of arguing, as well as uncovering one fundamental difference: Schopenhauer’s arguments start from examining the limits of one’s experience of the empirical world; from this, he draws conclusions about the thing-in-itself. Sankara, however, starts from assumptions about the nature of ultimate reality, and uses these to draw conclusions about our experiences of the empirical world.

1 See Berger (2004) and App (2006 and 2014) for more on the question of influence.

2 Magee, 1987: 316. By ‘Eastern thought,’ Magee is referring specifically to Hindu and Buddhist philosophy. 3 Kruijf and Sahoo, 2014: 105

4 Bartley, 2015: 180

5 Alston, 2004: 1, 23-26

6 A theory of representation could also propose that we perceive through representations instead of perceiving representations. In both cases, the point is that we don’t directly perceive an underlying thing as it is in itself.

7 Here I am primarily referring to Anquetil-Duperron’s Oupnek’hat, a Latin translation of the Persian Sirr-i Akbar, which in turn was a translation of fifty of the Upaniṣads. App (2006) argues that Schopenhauer’s first encounter with Indian philosophy was actually with a translation of the Bhagavad Gītā by Majer. For more, see Cross, 2013: 9-36 and App, 2006.

8 Primarily, I use the 6-volume Sankara Source Book by A. J. Alston, and the translation of both volumes of The World as Will and Representation by E. F. J. Payne. In the List of References, I provide a note on abbreviations used for primary sources.

9 A pronunciation guide for transliterated Sanskrit can be found in Bartley, 2005: 303.