The Third Rule of Magic

Share:

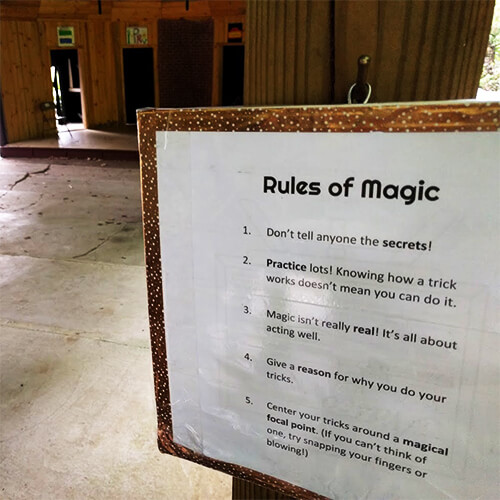

While working at Long Lake Camp for the Arts, where I taught magic to 8–16 year old kids for two and a half months, I wrote out five rules of magic for the kids.

These were by no means objective rules; instead were just ones I'd written myself. I wrote these specifically for helping 8–16 year olds learn how to perform magic well, and to match the tricks I was teaching.

Most wanted to learn card tricks, presumably due to my background in card magic and the prevalence of card magic in the media. As much as possible I tried to avoid mathematical tricks — while often self-working and therefore easy for children to learn, they have the tendency to be quite dry.

Tricks where cards were treated less as cards (i.e. where the suit / value of the card was important) and were treated more like ordinary objects were ideal. The main thing I was pushing was telling good stories, and giving reasons for doing the things that had to be done for the magic. Hence, avoiding dealing three piles of 7 cards and all that bs.

As a side note, a trick which was great for this was David Jade's Static. It ticks all the boxes; it:

- required some basic sleight of hand (namely learning a swing cut)

- involved creating a simple gimmick

- gave the kids a special prop to look after (responsibility + also exciting to have a secret prop!)

- was open-ended enough so that they could come up for their own story as to why the deck moves

- was a crazy powerful trick, that still used just a deck of cards, but looks miraculous when done right

If you’re a magician and don't do a haunted deck trick, I can't recommend this one enough. It’s so much less fiddly than the ‘classic’ way of doing a haunted deck and is totally hands-off when done on a table; you can even do it as a rising card in your own hand (like Eoin O'Hare's Sleeper). A really, really great trick.

Anyway, back to the rules. They were:

-

Don’t tell anyone the secrets!

-

Practice lots! Knowing how a trick works doesn’t mean you can do it.

-

Magic isn’t really real! It’s all about acting well.

-

Give a reason for why you do your tricks.

-

Center your tricks around a magical focal point. (If you can’t think of one, try snapping your fingers or blowing!)

I hope it’s clear how these tried to encourage the kids to give their magic performance a motivation or justification. We had lots of fun stories about Dr Strange and Himalayan monks and Matilda for the haunted deck plot.

Here I want to focus on rule 3.

Real Magic

“Magic isn’t real” isn’t something you’d normally think to teach children. But we had a lot of fun with it. Like all the above rules, it made them think more about why they were performing, and how to act as if it were real. Walking around the camp we also had some fun: we’d show people my hands were empty, cup them together, get someone to put their hands on my hands, get more people to join in, eventually gathering a big crowd. Then do a big, loud dramatic countdown, and then, at zero, shout ‘magic isn’t real!’ and run off.

Sometimes the kids were gutted by rule 3. I think everyone is when they find out that magic isn’t real. But it was important to have it in there, so that they realised they needed to act instead of just doing-the-moves. They came to realise that they themselves had to believe in the magic they did, in order for their audiences to believe in it.

But since coming home I’ve been reading some of my notes and books, and found an essay in a pamphlet by Benjamin Earl about real magic.

Earl advocates a paradigm shift. He suggests making...

He defines real magic by the following assumptions. We must assume that:

-

magic is real: it is a dimension of subjective experience

-

magic performances are comprised of real skills and real abilities

He also advocates developing language that is compatible with these assumptions.

His full post can be found here. I find this really interesting. It challenges the commonly held view that we, as magicians, have to be liars or have to deceive people. We can be genuine: not only in creating a genuine sense of wonder in our spectators, but in having the genuine belief that what the sense of wonder stems from is something really real.

Does this mean going so far as to be honest about methodology? Earl points out of Chan Canasta that:

Food for thought.

I've got more to say on this, linking it to notions of ‘real’ with a capital ‘R,’ i.e. a metaphysical thing-in-itself, and one of my favourite passages of philosophy, ‘How the true world finally became an error.’ But will save all that for another time.

Thanks for reading!

P